August 9, 2022

Rice Media

It was Monday, 9 August 1965 when Separation was announced. In Singapore, pockets of residents went about very ordinary affairs across the island. Couples were on dates watching Clarence The Cross-Eyed Lion at Lido Theatre. At the same time, over at Gay World Stadium, spectators gathered to witness the final match of the Singapore amateur open boxing championships.

Rice Media

It was Monday, 9 August 1965 when Separation was announced. In Singapore, pockets of residents went about very ordinary affairs across the island. Couples were on dates watching Clarence The Cross-Eyed Lion at Lido Theatre. At the same time, over at Gay World Stadium, spectators gathered to witness the final match of the Singapore amateur open boxing championships.

Somewhere up north, about 50 villagers, led by their MP Teong Eng Siong, were digging a drain in the Malay settlement of Kampong Tengah, now more commonly known as Sembawang.

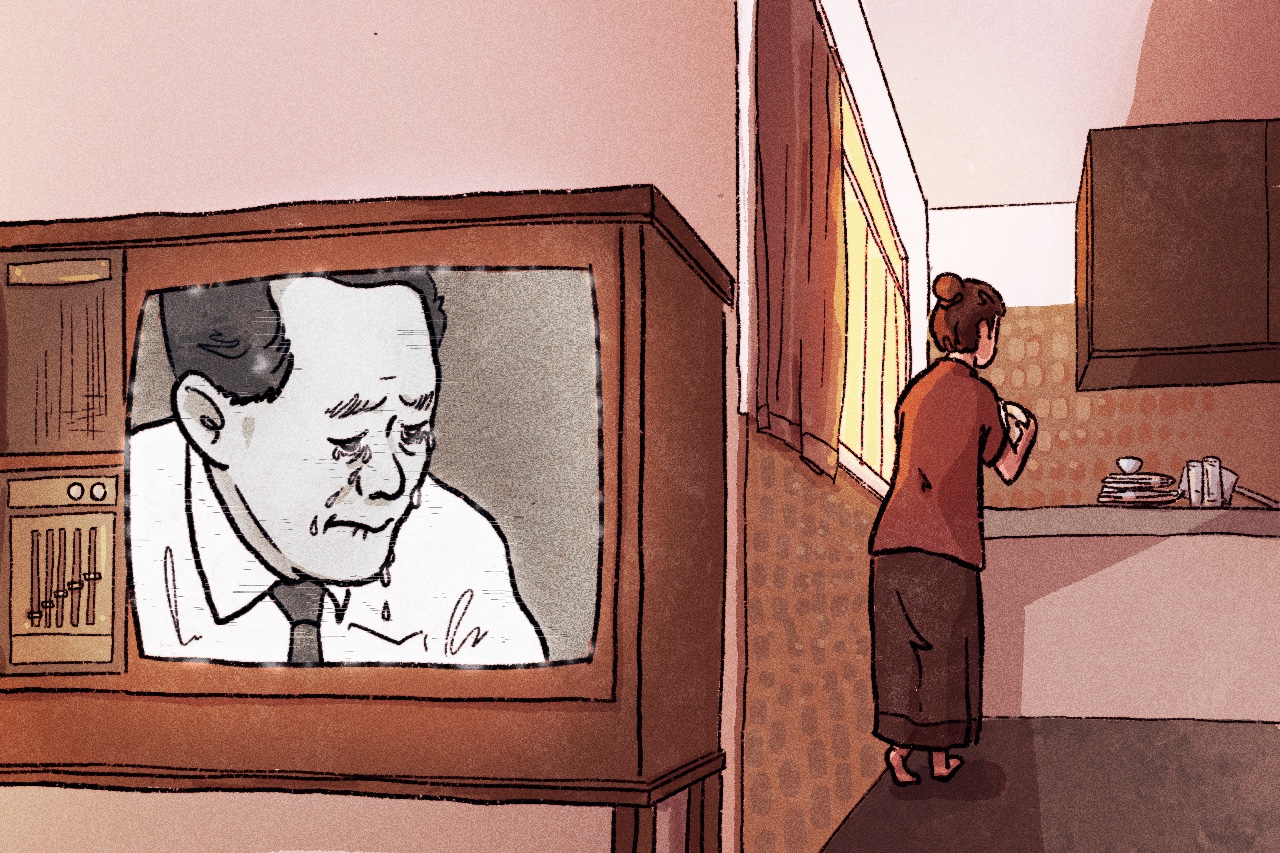

Amidst this humdrum routine goings-on, none would be more consequential than when former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew teared up on TV, his voice choking as he spoke about the Separation of Singapore from Malaysia.

“For me, it’s a moment of anguish because all my life … The whole of my adult life, I had believed in merger and the unity of these two territories. You know, it’s a people connected by geography, economics, and ties of kinship … would you mind if we stop for a while?”

[This is where most video will stop -- with the image of a despondent Lee Kuan Yew. A man not inclined to showing weakness or tears in public. It was a dramatic moment. Even Lee asked that they stop for a while for him to recover his composure. But... what happen after that? What did Lee say after he composed himself. This development so devastated him that he was overcome with emotions. And he had to pause for a while to recover his composure. I want to know what happened after that. I want to know what he said after that. I want to know how he overcame the devastating news, how he came to terms with the new reality, and how he decided to go forward. Because we did. But the media seems to only remember his distress, but not his recovery.]

It’s a lasting image, no doubt, of a political leader, usually stoic, determined, and firm. Now, through a small black and white television set, Lee looked tired, emotional, almost retrospective, as he addressed a group of journalists on the rationale behind the Separation.

But what of the masses who experienced the cusp of immense change? Four Singaporean seniors in their 70s share what they recall of the historic day. They tell us what they were doing when the news broke, what they observed, and what went through their minds.

But what of the masses who experienced the cusp of immense change? Four Singaporean seniors in their 70s share what they recall of the historic day. They tell us what they were doing when the news broke, what they observed, and what went through their minds.

“At 13, I wasn’t attuned to political affairs around me”

Julia D’Silva, 70, was a civil servant who retired in 2013 after stints in the Finance, Health, and Defence ministries. She was also chairperson of the Heritage Committee in the Eurasian Association for two terms, from 2016 to 2020.

During this period, she led a team to revamp the association’s heritage gallery by merging three separate galleries into one, which is now called the Eurasian Heritage Gallery.

Julia was 13 when Singapore separated from Malaysia.

When I was growing up during Singapore’s pre-independence years, it was a treat for us kids when our father drove us “up country” to places such as Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Port Dickson, Cameron Highlands, Penang, and Fraser’s Hill for a vacation during school holidays.

In those days, taking an airplane for a vacation to faraway countries was but a dream for most Singaporeans. For many people, a short break in Peninsular Malaysia, though near, was considered exciting. And it was undoubtedly the most affordable.

I was in Secondary One in 1965, studying in Raffles Girls’ Secondary School. During the August term break, my family and I travelled to Malaysia, as we often did, for a holiday. All six of us—my father, mother, elder brother, twin sister, younger sister, and me—were enjoying the drive back home in our family’s Opel Kapitan car.

We were on the way home when Separation was announced. This was either before we reached Kuala Lumpur or Aunty Mavis’ house. Aunty Mavis was the widow of Uncle Percy Proctor, my father’s close friend who had moved to Kuala Lumpur with his young family before the 1963 merger.

When I was growing up during Singapore’s pre-independence years, it was a treat for us kids when our father drove us “up country” to places such as Kuala Lumpur, Malacca, Port Dickson, Cameron Highlands, Penang, and Fraser’s Hill for a vacation during school holidays.

In those days, taking an airplane for a vacation to faraway countries was but a dream for most Singaporeans. For many people, a short break in Peninsular Malaysia, though near, was considered exciting. And it was undoubtedly the most affordable.

I was in Secondary One in 1965, studying in Raffles Girls’ Secondary School. During the August term break, my family and I travelled to Malaysia, as we often did, for a holiday. All six of us—my father, mother, elder brother, twin sister, younger sister, and me—were enjoying the drive back home in our family’s Opel Kapitan car.

We were on the way home when Separation was announced. This was either before we reached Kuala Lumpur or Aunty Mavis’ house. Aunty Mavis was the widow of Uncle Percy Proctor, my father’s close friend who had moved to Kuala Lumpur with his young family before the 1963 merger.

At 13, I wasn’t attuned to political affairs around me. Neither were my classmates. My father, a school inspector then, did not discuss political developments and issues with us.

Still, I could see the news perturbed him. He probably was afraid that the announcement could trigger wild reactions from both sides of the causeway.

My father wanted to hurry back to Singapore as quickly as possible, fearing trouble erupting along the way. So, after a short stop at Aunty Mavis’ house, we sped back anxiously to Singapore.

It was with great relief that we got through the Causeway without any trouble that evening.

The idea of nationhood didn’t occur to me yet on 9 August 1965. It only really dawned on me a year later when my twin sister and I participated in our first National Day Parade in 1966 with our school’s National Police Cadet Corps contingent.

We felt a burst of pride standing on the Padang, carrying the flag and marching past City Hall, where our president, prime minister and pioneer leaders were standing. To do it again the following year added exhilaration and pride.

“I reckon we were confident of Singapore as a country, even more so than the political leadership”

Conrad Raj, 75, is a retired journalist. For almost 40 years until 2013, he worked for newspapers such as The Business Times, The Straits Times, and Streats.

Known for his coverage of the collapse of British investment bank Barings in 1995 due to Nick Leeson’s multi-billion losses, Conrad uncovered the handwritten fax by the rogue trader addressed to the bank, which was an international scoop.

His last designation was Editor-at-Large at TODAY.

Conrad was 18 and in pre-university on the day Singapore became an independent nation.

When the bombshell dropped that morning, my father, a civil servant, told the family that he wanted to return to India. He didn’t trust the People’s Action Party—then new in government for only six years.

Every time Lee Kuan Yew came on the radio, he would switch it off. But 9 August 1965 was an exception.

Older Indians like my father were suspicious of the PAP. They worry that Singapore will become a Chinese state upon independence.

His displeasure also stemmed from a massive pay cut implemented across the civil service when the party first came into power. It affected him significantly as a clerk in the treasury department of the City Council.

Things were different for my mother. She spent most of her life before marriage in Selangor. Unlike my father, she was adamant about staying in Singapore and did not yearn to move to India.

For me, however, the news came as a shock even though I was aware that tensions were growing between the two powers. After hearing the news over the radio, my classmates and I phoned each other to find out what had happened. In the streets, police presence was visible, and the atmosphere was tense.

I also recall gathering at my friend’s house later that day, where we watched Mr Lee’s press conference on television.

Some residents were concerned that Separation would create more tensions between the races. Others cheered because they were fed up with the constant racial tensions while we were in Malaysia. It was a situation exacerbated by Lee Kuan Yew, who was insistent on a Malaysian Malaysia.

Even Malaysian Chinese politicians like Tan Siew Sin were wary about Singapore’s cockiness.

The discussion among Singaporeans over Separation went on for weeks. The unemployment rate back then was still high. Among the older people, they wondered if we could survive as a nation.

Youths like us, however, were more optimistic. I reckon we were confident of Singapore as a country, even more so than the political leadership. We didn’t think we would be down on our knees or harbour regret that we were out of Malaysia.

[Is there a word for irrational optimism? Optimistic because one does not know any better? Optimistic because one does not realise the possible problems and hazards? Oh yeah, "youthful optimism".

I think this was the right sentiment—Singapore wouldn’t have pulled through otherwise.

At the time, I was living in a two-storey government terrace house in Hooper Road, situated in the Newton area. It was a middle-class, mixed-race community where people were more educated.

Several Eurasian families, one related to K.M. Byrne (a PAP founding father), celebrated the announcement. Other than that, sentiments were generally muted.

And despite concerns over racial tensions in the aftermath of Separation, there wasn’t any change in dynamics between our neighbours along Hooper Road.

The Separation didn’t affect the camaraderie we enjoyed; we still played football together and went to each other’s houses.

One or two Chinese families eventually migrated to Australia and Sarawak because they didn’t trust the PAP to govern a post-1965 Singapore.

I think this was the right sentiment—Singapore wouldn’t have pulled through otherwise.

At the time, I was living in a two-storey government terrace house in Hooper Road, situated in the Newton area. It was a middle-class, mixed-race community where people were more educated.

Several Eurasian families, one related to K.M. Byrne (a PAP founding father), celebrated the announcement. Other than that, sentiments were generally muted.

And despite concerns over racial tensions in the aftermath of Separation, there wasn’t any change in dynamics between our neighbours along Hooper Road.

The Separation didn’t affect the camaraderie we enjoyed; we still played football together and went to each other’s houses.

One or two Chinese families eventually migrated to Australia and Sarawak because they didn’t trust the PAP to govern a post-1965 Singapore.

“We were relieved to be out as we had many problems in the Federation”

Massamah Awi, 79, is a retired teacher who, in her earlier years, taught English as a second language. Although Massamah officially retired in 1988, she continues to teach in primary schools on an ad-hoc basis.

She was 22 and teaching at Guillemard Malay School when she witnessed Singapore’s split from Malaysia.

As a former teacher, educating pupils about Singapore’s history was part of National Education lessons. During these classes, the topic of Separation would come up, often sparking lengthy discussions. And rightfully so, given how the split with Malaysia is the raison d’etre of our nationhood.

Separation then, at least to lay people like me, was a muted affair. I married in February that year and lived with my late husband at Block 1 Changi Road in a three-room rented Housing Board flat. It’s since been demolished and replaced with Geylang Serai Market and Food Centre.

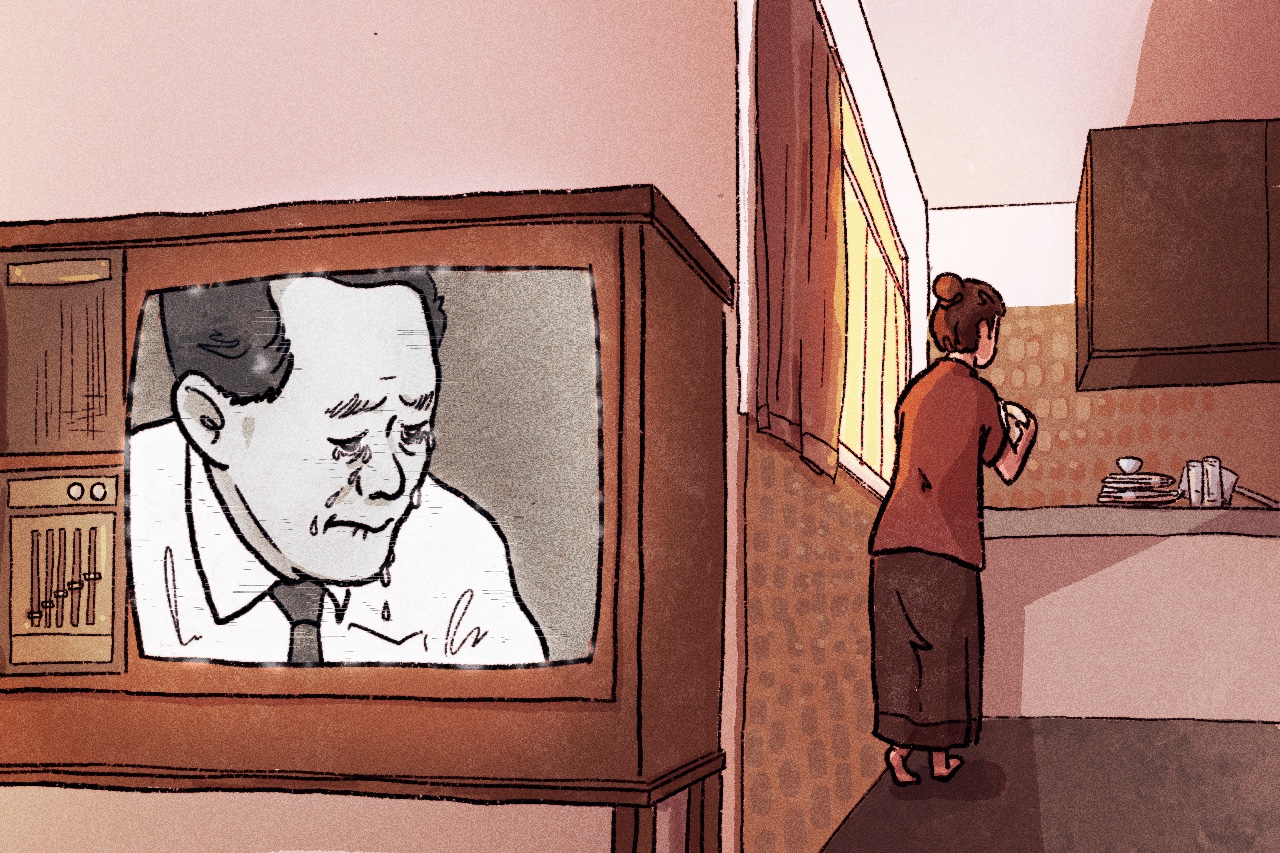

On the afternoon of 9 August, I remember I was alone at home in the kitchen preparing for dinner. Like many others then, we couldn’t afford a television set, so I missed the news of Separation when it was announced. I found out from my husband, a policeman, who came home after work with the news.

“We all no more Malaysia, you know?” he told me, calm and matter-of-fact.

I was nonchalant about the whole affair as I wasn’t interested in politics. It was the same for the neighbours around me—no commotion, public demonstration or celebrations.

Life went on as usual—we went to the market, to work, and so on. My husband wasn’t activated for special duties on that day either. Even later, when we had passport controls at the land checkpoints, the move didn’t affect me much since I seldom travelled to Johor Bahru.

And when I returned to school the next day, neither the students, my colleagues, nor the principal cared enough to talk about it. Perhaps this was the prevailing attitude of the time: docile and taking life as it is.

While there wasn’t fear or triumph surrounding Separation, we were relieved to be out as we had many problems in the Federation. The politicians from both countries were often at loggerheads.

Some of us even believed that the Malaysians didn’t want us, which was why they sacked us from the Federation. I thought: sack lah. We can also survive. (author’s note: The secret “Albatross” file, declassified in 2015, revealed that Separation was a negotiated process between both governments, contrary to the popular portrayal that Separation was foisted upon Singapore by Malaysia)

[The comment on the "Albatross" file and the "conclusion" that Separation was a mutually agreed decision between Malaysia and Singapore, glosses over 2 things. First, it has been presented that Malaysia had ejected Singapore from the Federation. This was NOT refuted either by Malaysia or by Singapore. Thus what is clear is that whatever the reality or actuality of this "negotiated separation", it appeared that Malaysia, for whatever reason chose to interpret or chose to present Separation, as the Federation ejecting a component member of the Federation. AND, Singapore did not disagree. Singapore did not refute. Singapore did not counter the "official" position with, say, a statement that we had in fact seceded from the Federation. Or at the very least, push forward a more neutral position that this Separation was a mutually agreed and negotiated position.

She was 22 and teaching at Guillemard Malay School when she witnessed Singapore’s split from Malaysia.

As a former teacher, educating pupils about Singapore’s history was part of National Education lessons. During these classes, the topic of Separation would come up, often sparking lengthy discussions. And rightfully so, given how the split with Malaysia is the raison d’etre of our nationhood.

Separation then, at least to lay people like me, was a muted affair. I married in February that year and lived with my late husband at Block 1 Changi Road in a three-room rented Housing Board flat. It’s since been demolished and replaced with Geylang Serai Market and Food Centre.

On the afternoon of 9 August, I remember I was alone at home in the kitchen preparing for dinner. Like many others then, we couldn’t afford a television set, so I missed the news of Separation when it was announced. I found out from my husband, a policeman, who came home after work with the news.

“We all no more Malaysia, you know?” he told me, calm and matter-of-fact.

I was nonchalant about the whole affair as I wasn’t interested in politics. It was the same for the neighbours around me—no commotion, public demonstration or celebrations.

Life went on as usual—we went to the market, to work, and so on. My husband wasn’t activated for special duties on that day either. Even later, when we had passport controls at the land checkpoints, the move didn’t affect me much since I seldom travelled to Johor Bahru.

And when I returned to school the next day, neither the students, my colleagues, nor the principal cared enough to talk about it. Perhaps this was the prevailing attitude of the time: docile and taking life as it is.

While there wasn’t fear or triumph surrounding Separation, we were relieved to be out as we had many problems in the Federation. The politicians from both countries were often at loggerheads.

Some of us even believed that the Malaysians didn’t want us, which was why they sacked us from the Federation. I thought: sack lah. We can also survive. (author’s note: The secret “Albatross” file, declassified in 2015, revealed that Separation was a negotiated process between both governments, contrary to the popular portrayal that Separation was foisted upon Singapore by Malaysia)

[The comment on the "Albatross" file and the "conclusion" that Separation was a mutually agreed decision between Malaysia and Singapore, glosses over 2 things. First, it has been presented that Malaysia had ejected Singapore from the Federation. This was NOT refuted either by Malaysia or by Singapore. Thus what is clear is that whatever the reality or actuality of this "negotiated separation", it appeared that Malaysia, for whatever reason chose to interpret or chose to present Separation, as the Federation ejecting a component member of the Federation. AND, Singapore did not disagree. Singapore did not refute. Singapore did not counter the "official" position with, say, a statement that we had in fact seceded from the Federation. Or at the very least, push forward a more neutral position that this Separation was a mutually agreed and negotiated position.

Second, Tunku Abdul Rahman first proposed "hiving off" Singapore to a confederation status with a looser union where Singapore would have complete autonomy except in the areas of defence and foreign affairs. Lee Kuan Yew had then authorised Goh Keng Swee to negotiate with the Malaysian leaders on the "rearrangement of Malaysia". Lee was hoping that a looser union with Malaysia would still allow Singapore access to the common market and other economic benefits, without interference from KL, but Singapore would give up our ability to influence events in the Federation. Goh however, persuaded the Malaysian leaders that only the complete secession of Singapore was feasible. Somehow he persuaded them that Singapore had to be completely separate from the Federation, not even a looser confederation would work. But what was not in his notes was why it was "decided" that it would be publicly presented as the Federation "expelling" Singapore from the Federation, rather than a more neutral, dignified, mutually agreed Separation. Somehow the conventional narrative served the Federation and Singapore's purposes. What those purposes might be, were not recorded.]

My late brother, serving in the military as a sergeant, decided to be a Malaysian citizen. After Separation, he was given a choice: continue to serve in the Singapore Army or join the Malaysian troops. Even though he chose the latter, we respected his choice, and it wasn’t an issue within the family. So familial ties weren’t affected.

Winston Wong, 75, is a retired soldier. In 1969, he founded the Bomb Disposal Unit, now known as the Explosive Ordnance Disposal Unit.

With the impending British withdrawal, Winston was trained as a Mine Clearance Diver in the United Kingdom to take over the Royal Navy Diving Unit at HMS Terror. In 1985, Winston was seconded to the Singapore Civil Defence Force to develop the Civil Defence Academy.

He left the Singapore Armed Forces in 1990 and was later appointed as an explosive domain expert at the Home Affairs Ministry until his retirement in 2018.

Winston is now a heritage tour guide at The Barracks Hotel Sentosa and runs a vintage shop By My Old School with his daughter.

He was 17 when the Separation happened.

I remember standing on a chair, cleaning the windows of my family’s ground floor Singapore Improvement Trust flat (also known as Princess Elizabeth II flats) in Farrer Park, when news about the Separation was announced on the radio.

I was in disbelief. Back then, I was a student at Gan Eng Seng School, located along Anson Road. I had to pass the City Hall area with all its colonial buildings when I travelled from home to school. En route, I would see decorations and banners hung from light poles and pillars with slogans such as “Malaysia for Malaysians”. These were put up to acclimate us to Singapore being part of Malaysia.

Still, while Separation was sudden, we never believed we could or would be a “Malaysian Malaysia”. We saw how the Malay politicians in Malaysia wanted to dominate everything, and Lee Kuan Yew would never give in to that.

Nevertheless, Mr Lee had a vision for Singapore. Separation was the only way out when the conditions couldn’t be met.

For students from the Chinese schools, it was cause for celebration, having previously protested against the 1963 merger. They were vocal and thought that with countries in the region gaining independence, why not Singapore too? The students feared losing our identity as the country with the most populous Chinese population in the region.

Many were also influenced by the Malayan Communist Party, which fought hard for decolonisation.

Residents who lived in Barisan Sosialis-controlled enclaves such as Jurong would have perceived Separation as a positive move. Barisan Sosialis had been against the merger, so it was easy to convince business owners, hawkers, and farmers in those areas of the benefits Separation brought.

My late brother, serving in the military as a sergeant, decided to be a Malaysian citizen. After Separation, he was given a choice: continue to serve in the Singapore Army or join the Malaysian troops. Even though he chose the latter, we respected his choice, and it wasn’t an issue within the family. So familial ties weren’t affected.

“We saw how the Malay politicians in Malaysia wanted to dominate everything, and Lee Kuan Yew would never give in to that”

| Winston in his younger days. (Image: Winston Wong) |

Winston Wong, 75, is a retired soldier. In 1969, he founded the Bomb Disposal Unit, now known as the Explosive Ordnance Disposal Unit.

With the impending British withdrawal, Winston was trained as a Mine Clearance Diver in the United Kingdom to take over the Royal Navy Diving Unit at HMS Terror. In 1985, Winston was seconded to the Singapore Civil Defence Force to develop the Civil Defence Academy.

He left the Singapore Armed Forces in 1990 and was later appointed as an explosive domain expert at the Home Affairs Ministry until his retirement in 2018.

Winston is now a heritage tour guide at The Barracks Hotel Sentosa and runs a vintage shop By My Old School with his daughter.

He was 17 when the Separation happened.

I remember standing on a chair, cleaning the windows of my family’s ground floor Singapore Improvement Trust flat (also known as Princess Elizabeth II flats) in Farrer Park, when news about the Separation was announced on the radio.

I was in disbelief. Back then, I was a student at Gan Eng Seng School, located along Anson Road. I had to pass the City Hall area with all its colonial buildings when I travelled from home to school. En route, I would see decorations and banners hung from light poles and pillars with slogans such as “Malaysia for Malaysians”. These were put up to acclimate us to Singapore being part of Malaysia.

Still, while Separation was sudden, we never believed we could or would be a “Malaysian Malaysia”. We saw how the Malay politicians in Malaysia wanted to dominate everything, and Lee Kuan Yew would never give in to that.

Nevertheless, Mr Lee had a vision for Singapore. Separation was the only way out when the conditions couldn’t be met.

For students from the Chinese schools, it was cause for celebration, having previously protested against the 1963 merger. They were vocal and thought that with countries in the region gaining independence, why not Singapore too? The students feared losing our identity as the country with the most populous Chinese population in the region.

Many were also influenced by the Malayan Communist Party, which fought hard for decolonisation.

Residents who lived in Barisan Sosialis-controlled enclaves such as Jurong would have perceived Separation as a positive move. Barisan Sosialis had been against the merger, so it was easy to convince business owners, hawkers, and farmers in those areas of the benefits Separation brought.

[If Barisan Sosialis were against Merger, then Separation would have been their vindication. And in the 1968 GE, they could have campaigned on the "I told you so" platform. Instead Barian Sosialis boycotted the election on the grounds that Singapore's independence was "phoney". What was the real reason? Speculation: 1) If they had won (because they had been against Merger in the first place) they would have been responsible for leading Singapore to success. And they had NO IDEA how to do so. 2) Better to let PAP win the GE, then lead Singapore into disaster, then BS come back in the next GE and "rescue" Singapore! 3) LKY was right that the BS (and pro-communists) wanted to disguise their communists objective as "anti-colonialism" or "anti-imperialism", but if Singapore is truly independent, then their objective would clearly be in opposition to an independent, non-colonial govt and would be exposed.]

But the idea of Separation didn’t significantly impact the rest of us, especially those who lived in the central regions. Even homemakers, who would gather and talk in the evenings, didn’t gossip about this.

We were not political then and were more worried about our livelihoods. The take-home wage per household at the time was about S$400 (S$1,600 in today’s terms). Although daily expenses were not that big of a struggle, many people lived from hand to mouth, paycheck to paycheck.

That was probably why people weren’t as bothered about the whole political situation, significant as it may be.

But the idea of Separation didn’t significantly impact the rest of us, especially those who lived in the central regions. Even homemakers, who would gather and talk in the evenings, didn’t gossip about this.

We were not political then and were more worried about our livelihoods. The take-home wage per household at the time was about S$400 (S$1,600 in today’s terms). Although daily expenses were not that big of a struggle, many people lived from hand to mouth, paycheck to paycheck.

That was probably why people weren’t as bothered about the whole political situation, significant as it may be.

No comments:

Post a Comment